Tobias and I made it and conquered the 1,860 km and around 33,000 HM at this year’s Silk Road Mountain Race as team “Salsaletten”. And you really have to say conquered, because it was very hard and exhausting work.

After 13.5 days we arrived happily at the finish in Balykchy at Lake Issyl Kul. We were also happy because we came 37th out of 98 riders who started in Talas, or arrived at all. This is because the drop-out rate this year was around 55% (and is actually even higher otherwise).

Almost 14 days is a long time, as the days blur and consist mostly of sleep-eat-ride-repeat. However, I can remember many experiences and places better than I did during the Atlas Mountain Race.

But a chronological narrative doesn’t make sense, which is why I simply asked myself questions about the race.

Have fun!

What is the SRMR and what makes it so special?

The Silk Road Mountain Race is considered the most challenging/hardest ultra bikepacking race in the world. It is ridden in self-supply mode and involves covering 1,860 km and 33,000 metres of altitude. After 2018 and 2019, it took place for the third time this year. This time, the route was even longer than in the previous editions, which made it a bit more challenging.

Also new this year: instead of starting in Bishkek, the start was moved to Talas, a town 300 km west of Bishkek, where the race was scheduled to start at 10 pm on 13 August.

Unfortunately, this did not quite work out, because the transport of the riders from Bishkek to Talas and especially the transport of the bikes in two trucks was delayed. So we arrived in Talas around 10 pm, but the bikes were not there yet. So we waited in a hotel restaurant until midnight to go to a hotel and get some sleep. The trucks were stuck on the route and were not due to arrive until 6am.

Then suddenly at 3.30 a.m. a wake-up call: the trucks would be there, everybody out, start is 4.30 a.m.. So we had to wake up quickly, get dressed and look for the bike. We briefly checked the bikes, quickly prepared ourselves and then the Silk Road Mountain Race started in the cool morning of 14 August.

One thing that is special about the SRMR is the climatic and landscape challenges. These are temperatures between -15 and +40 degrees, sometimes within one day. In addition, wind, rain, snow, frost and all that in a high alpine country. In this year’s Silk Road Mountain Race we had to overcome 16 mountain passes higher than 3,000m. And not all of them were really rideable and sometimes only to be climbed or pushed due to landslides.

The paths and roads are often corrugated iron tracks, rough gravel roads, mountain paths or trails. All this adds up to an average speed of about 10 km/h and a considerable strain on people and equipment.

On the other hand, the length of time can be quite demanding, especially mentally. While in Morocco everything is over after 7 days in the AMR, in the SRMR you are still in the middle of the race. And mostly somewhere in the middle of nowhere, in a lonely valley or on a high pass or in the backcountry at the Chinese border. From my point of view, the physical strain is higher in Kyrgyzstan, which of course also affects mental motivation and stamina.

Why do you do it, what attracts you to such races?

I travelled the world by bike for many years as a classic bike traveller. In 2018, I became aware of the Tuscany Trail and, with it, of bikepacking as an alternative and complement to cycle touring. The Tuscany Trail is now more of a leisurely event, but you ride over trails and tracks and discover completely new sides of a landscape. A little later, I was also on the road as a bikepacker in Kenya and Tanzania.

At the same time, I became more and more involved in the bikepacking scene and also became aware of the Silk Road Mountain Race. I found this sporty way of bikepacking and the combination of performance and adventure very attractive. A few months later the Atlas Mountain Race was announced and that was the starting signal for me to change from a bike traveller to a bikepacker to an (ultra)long-distance endurance bikepacker through training and appropriate preparations. With the Silk Road Mountain Race, I have now fulfilled my dream of competing in the toughest of these races and passing.

Travelling the world by bike was already impressive and eventful, but somehow I needed something different. I wanted to test my performance limits, see how far I could go physically, test how strong I was mentally and combine all this with my passion for adventure on the bike and discovering new countries and landscapes. And that’s what the Atlas Mountain Race and the Silk Road Mountain Race offered me.

And in the end, the rather silly answer to such questions is: I do it simply because I can. And for that I am very grateful.

What impressed you most on the road?

There were many things: of course, and above all the country and its landscapes. Huge mountain ranges, snow-covered peaks, lonely yurts and countless horses, cattle and sheep in endless valleys and up to remote mountain passes.

Sometimes you feel quite tiny, cycling 90 km to a pass through a high valley, or rolling down from a mountain into civilisation.

Rainstorm with the chance of fresh snow

I was also impressed by the climate and weather: within a few hours the weather could change from warm sunshine to rain, hail and finally snow. Only to change again just as quickly.

Right at the beginning, we had only been on the road for a few days, the rain caught up with us on an ascent to a pass. It poured all night and the next morning the rain turned to snow and a little later we were pushing our bikes through 20-30 cm of fresh snow.

The end of the power?

Less great, but just as impressive and interesting were the effects of the efforts on the body. For example, I had to struggle with an absolute weakness for a few days. We were on the ascent to the 3,800m Arabel Pass when I noticed that my legs could no longer build up any strength.

My muscles felt unable to pedal watts at all. It always took some time before the power could reach my legs and then it was usually not enough. Therefore, riding was unbearably exhausting and I had to take breaks again and again because I couldn’t really climb even the smallest slopes. I was drained, exhausted.

Tobias then motivated me up the serpentines to the Arabel, with the result that when we reached the top we still had to ride the 17km over the Arabel Plateau, which lies at an altitude of 3,800m. It was night time by now and we didn’t want to risk an overnight stay at this altitude and in these cold temperatures. In view of my poor form, this was of course not ideal. And when we made it, I had to stop again and again on the descent in the endless serpentines because my body was so weak and I was freezing so much that concentrated driving was hardly possible.

After a night with a little more sleep, things were better, but the next monster, the Tossor Pass, was waiting for us. But somehow I managed this one, too, and in the end I was even able to push the passages that were blocked by a landslide quite quickly. I was very surprised that I could find such strength.

The longest day

All the more so because the following day I was still struggling a lot with my physical weakness. I had reacted to it in the meantime, eaten more than usual, taken more minerals and it was slowly getting better. But then came Check Point 2 and with it the longest and hardest day of my bikepacking life so far, starting with the Old Soviet Road.

This is an old military road in the Kyrgyz-Chinese border area, which is more than 30% steep and had to be pushed up. It was so steep that I could only push the bike a few metres at a time to catch my breath and gather strength. This went on for 1.5 km. And when I finally reached the top, another 20 kilometres awaited me through the hilly meadow landscape, peppered with old barbed wire remnants and steep climbs and descents. I had a lot of respect for this track, also because I was just not in shape. Nevertheless, I managed to master it well.

But that was not all: Now the track led 80 km along the Chinese border on a monotonous corrugated iron road and with alternating strong headwinds. So we put our heads down and pedalled as best we could. It didn’t go so well, as there was often no rideable track and cycling was like jumping back and forth along the path.

Of course, a thunderstorm also passed by, but that couldn’t spoil the mood. The mood was dampened, however, by a seemingly flat 13 km that led directly to the start of the climb to the Tash Rabat Pass. However, they turned out to be 13 flat kilometres that led over a dry lake and were thus quite bumpy and not very rideable.

So it was already dark when we started the climb to the Tash Rabat pass. Our expectation was a short but steep track up to the pass and then a corresponding descent to a yurt village only a few kilometres away, where we wanted to sleep. In fact, the track turned into a rocky valley and we had to climb up the steep mountain side on loose scree in the dark, only to descend again in the same way on the other side.

With the steep slopes of more than 20%, riding was out of the question. And so we set up our tents during the night on the way down into the valley. The longest day lay behind us and it began as it ended: with pushing and hike-a-bike in its most extreme form.

Who loves his bike, climbs

And because it was so nice: hiking with the bike is an integral part of the Silk Road Mountain Race. And especially at the end of the race, on the last kilometres, race director Nelson added a character test: 25 km hike-a-bike over three mountain passes, the last of which is the highest at almost 3,400m.

The special thing about it is that there is very little riding involved. Instead, it’s all uphill on very steep hiking paths and trails. To give you an idea of the challenge: it took us 6 hours to cover 5 km.

All in all, we needed 12 hours for this segment of the race and had to pitch our tents again in between, as we had lost the track and Tobias had also developed problems with his legs.

So even though it was more type-2 fun – this section of the race impressed me, also because it led through a beautiful landscape that reminded me a lot of the Alps. Only I couldn’t really appreciate it because of the effort….

I was also impressed by the performance of the Czech rider Martin Pisacka (Cap 44): we kept running into each other and after the Kegeti Pass, we suddenly met him in the village of Kegeti. His freewheel was broken and he could not ride anymore.

But instead of giving up, Martin decided to walk the remaining 200 km. And he managed to do so, reaching the finish line more than in time, where we of course celebrated him accordingly. An impressive performance!

Were there also weak moments and did you think about giving up?

There were definitely weak moments. And they were very educative. I tend to be very stable mentally, but in Kyrgyzstan I did reach my limits from time to time, or rather reached new areas of stress. There was never the will to simply give up. But there was a willingness to say “if something happens to the bike now, then I can finally stop”. That is, a rather untypical delegation of giving up to the bike, to external reasons with which I can correspond to an inner urge. But the bikes have lasted, and they don’t break that quickly and can be repaired.

In the days when I was physically (supposedly) very weak and at my performance limit, I actually thought about giving up. But more along the lines of: do you want to do this race like this? That’s more torture than fun. It just took me a while to understand that this is part of the race.

How was the supply on the way?

Actually good. With a few exceptions, there was enough water everywhere. We always filtered the water (Be Free is a very good filter) or disinfected it (Micropur).

When it came to food, we were also well prepared: we each had 4 portions of high-calorie expedition food (800-1,000 kcal per portion) with us. In addition, we stocked up on ice cream, biscuits, Snickers, bag noodle soups, bread, cheese and fish in the shops along the way.

The longest section of the route without a supply point was 240km long. And even so, we often had to bridge distances of 160 to 200 km with appropriate stocking up. But that always worked out well and we never had any supply problems or food shortages.

As a general rule, however, we did not eat meat or milk during the race. The risk of infection was simply too high. We did well and didn’t have any stomach problems.

How was it this time as a pair with Tobias?

More intense. That has to do with the length of the race and the higher mental load this time.

We grew closer and closer together as a team, motivated and supported each other in the weak moments. I found that very good, also because I am more of a soloist.

I was happy to be able to ride the SRMR with Tobias. I was mentally prepared for him and if he had dropped out, it would have been much harder for me to finish the race.

I would also do races like the AMR or SRMR on my own. But then you need a different preparation.

Equipment: Were there any damages & failures? And what are your tops & flops?

Fortunately, we got through the race without any major mishaps. However, the biggest breakdown and challenge was when Tobias’ seatpost broke 7 km before CP 2.

And you can call it Trail Magic that in CP2 there was a rider who had to give up due to indigestion/food poisoning and whose seatpost fitted Tobias exactly. So we went on without further delay.

Apart from that we had some holes in the tubeless tyres. But we were able to get them under control with Maxalami and new sealing milk, so we rode the whole race tubeless. I had a stone put a hole in the back of my tyre and also a crack on the side at the contact point between the tyre and the rim. I got both sealed with Maxalami and it lasted for more than 1,400 km. Overall, the Vittoria Mezcal tyres have convinced me again. They are currently the best tyres for this kind of challenge from my point of view and experience.

Otherwise, there were only slight failures due to screws coming loose. But that was quickly remedied and not relevant. Unfortunately, one bottle cage broke off for me. First the screw broke off and then the holder tore through.

What took a bit longer was Tobias’ loose cassette. For a while we had to tighten it again and again because the locking ring of the Sunrace cassette kept coming loose due to the shaking. By the way, this did not only affect Tobias, but other riders also had to struggle with it. But we were able to tighten the cassette with the Unior tool and a tent ring.

As we noticed, there were often tyre problems (slashed by the stones), broken spokes, broken freewheels, pedals that fell off, broken cranks, defective bottom brackets and damaged brakes/brake levers.

Right at the beginning, while still acclimatising, one of the fastener sides of Tobias’ Revelate Designs Saltyroll ripped in or off. That was surprising, but also annoying. We rolled it up and Tobias loaded the Saltyroll from one side only throughout the race.

I especially liked the following things:

- Forclaz over-gloves: they reliably protected the gloves in rain and cold wind and added warmth. They are lightweight, easy to stow and incredibly practical.

- Be Free water filter: Unfortunately, my Sawyer water filter failed right at the start, so we used Tobias’ Be Free. Extremely practical, quick and easy to keep clean. I will also get this one.

- Big Agnes Copper Spur HV UL 1 Bikepack: The tent was really great. Self standing and big enough to fully dress and pack everything inside. Easy and quick to set up and take down. Very compact to stow away and quick to dry if it got packed up wet (which happened all the time). Also ideal for tall people like Tobias with his 1.97m, as the side walls rise more steeply, leaving enough space for a sleeping mat and sleeping bag (especially in the foot area). It is also quite spacious.

- Garbarauk: I have to say that the conversion to a Garbarauk gear cage and rollers as well as a cassette (10-50) was worth it. The Rival works so well and smoothly with MTB cassettes. The shifting performance was very good, especially when it came to the steep climbs, it controlled the 50 without flinching. I rode the SRMR with a gear ratio of 30 (oval) at the front and 10-50 at the rear.

- Pedaled Alpha Jacket: I am a fan of the Polartec Alpha material. It’s very light, breathable and above all very warm. That makes it a bit more expensive, but it’s worth it from my point of view. I therefore got the Pedaled Alpha jacket, which I actually wore all the time. It was so good and warm that I didn’t need my down jacket once and instead always just used the combination of Alpha and rain jacket. That was completely sufficient in cold weather with wind, snow and rain. Or in the evening in front of the tent.

- Klite USB charger: I am very fond of the Klite Bikepacker Ultra V2 lamp anyway. The Klite USB charger is also included. And it was so efficient and good that I was not only able to charge the Wahoo (100%), but also my iPhone 12 at the same time, even though we only had a few passages where we could ride really fast. The charger already starts at low speeds and delivers reasonable energy. Of course, this is also due to the SON 28 hub dynamo. So we hardly needed our power banks.

- Cumulus X-Lite 400 sleeping bag: At just about 600g, the customised Cumulus fully met my warmth expectations in Kyrgyzstan. I had it built with Toray fabric and hydrophobic down and only had Pertex Quantum fitted in the foot area and inside the hood. Even in temperatures below freezing, it didn’t let me down. Since physical exertion often increases the feeling of cold, I also had the Cocoon Expedition Inliner with me. This inner sleeping bag is supposed to provide up to 5 degrees more temperature and, in addition to effective protection against dirt, also offered me more comfort. All in all, a great combination. Note: the Toray weave makes the sleeping bag very smooth. This means you also slip faster on the sleeping pad. This can sometimes be funny, especially if you don’t sleep on level ground.

I/we have not had such good experiences with the following equipment:

- Wahoo ELEMNT Roam: We still celebrated this one to the AMR because of its long battery life and precision. In Kyrgyzstan, however, it had a few weaknesses: for example, it didn’t always completely record the ride (though you might be able to change that by turning off the auto-pause function). More importantly, it did not always find the track accurately, which was already difficult with the Hike-a-Bike. And he always turned the track orientation to the west when taking a break. So when you’re moving, the track is always aligned directly in front of you. When you take a break, the Wahoo turns it 90 degrees. I don’t know why. It’s just stupid when you want to see and check the track during breaks and then only get crap displayed. In addition, my Wahoo switched off 4-5 times or stopped measuring. Only after a restart was the tour restored, which costs time, however.

- Sealskinz socks: In fact, these socks are waterproof – at least that’s what the advertising claims. In practice in Kyrgyzstan, unfortunately, these socks were not waterproof at all. On the contrary: a light river crossing with only splashing water or shoes slightly standing in water was enough to get the feet wet. So the socks were only good as protection against the cold and wind. A pity really.

- Zip rain jacket: This is complaining on a high level, but the zips of my Mountain Equipment Skardu jacket were quite stiff and difficult to operate with one hand. Overall, however, I was very satisfied with the performance of the jacket and will have the hood sewn a little more suitable for cycling.

- Restrap Stem Bags: I rode with two of the Restrap Stem Bags on the handlebars. One held a bottle and the other food. They are ok so far, but too narrow and too heavy to offer any real advantage. I will probably replace them with Revelate Design Mountain Feed bags, also because they are big enough and more accessible to hold cooking utensils or food.

- Ortlieb saddle bag: Tobias rode with this bag and unusually it delaminated and fell apart. It was interesting to see how the seams opened up. Unfortunately, it was no longer waterproof, but we were able to help ourselves with plastic bags. Other riders had the same experience and complained about damage to the handlebar pulley (cracks) and saddle bag (seams and connections opened). I am still convinced of Ortlieb quality, but I found this quite remarkable.

- Revelate Designs Spinelock, Ripio & Saltyroll: With the Spinelock, at some point it became increasingly difficult to put the spin through. This was mainly due to the persistent dirt. So you should always clean this pin and also the corresponding channel on the bag. The function was never affected, only the attachment was a bit more difficult. With the Ripio frame bag, I noticed that the zip pulled out threads. That doesn’t have to be in this price range. I cut it off. Less pleasing was that in the lower bag, things rubbed a kind of hole into the first inner coating. I can patch that and it’s not a hole to the outside. But I would have expected more resistance here. And of course Tobias’ Saltyroll, where the entire roll closure almost tore off once all around when he tried to compress the roll. That will be a material defect and a warranty case.

Was the Salsa Fargo the right bike for the Race?

Yes and no.

Yes, because the Fargo is basically a bike for exactly such challenges. It has the appropriate geometry, offers the necessary tyre width and has enough options to make necessary attachments.

No, because races like the AMR and SRMR actually require hardtail MTBs. Ideally with suspension forks, hydraulic brakes and flat bars. In my view, these are the better or more suitable bikes for the terrain and the demands of the courses.

In any case, the equipment on our Fargo was convincing and nothing really broke. They are very robust drop bar MTBs that can take a lot of punishment. In Kyrgyzstan, some suspension and brakes with more power (4 pistons) would have been even better.

How did you prepare yourselves?

You can’t really prepare for a race like the Silk Road Mountain Race. We put a lot of time and energy into a physical training plan, with which we trained intervals and long distances in a structured way for almost a year.

We also spent a lot of time studying the course and its characteristics, and of course benefited from our experiences at the Atlas Mountain Race.

I trained more long distance this time and did a lot of longer rides. And in June, Tobias and I met again in the Harz mountains for a small training weekend to discuss final details.

You can read more about the training and preparation here.

What marks did the SRMR leave behind?

Mentally or spiritually, a high level of satisfaction. I am very proud to have passed this adventure. The experience of almost giving up, being at the end of my tether and then having the strength to finish was very interesting and formative. I’m not an emotional person, but that surprised me.

The Silk Road also left its mark physically: a bruised rib, for example, which I sustained in a calculated fall in a sand field shortly before the finish. It will painfully accompany me for a while.

Then there are numb toes again this time. That will take a few months to go away. Apart from that, I have the normal symptoms of the lack of performance: thick hands and feet, restless legs, headaches and a slight exhaustion. But everything is normal so far.

And I make no secret of the fact that finishing this race successfully is also important to me because it gives me credibility as a podcaster and blogger. I couldn’t write and speak about all these topics with a clear conscience if I wasn’t able to do them myself. That may sound strange, but it’s very important to me and also has a lot to do with self-respect.

But now I can show off and call myself an ultra 🙂 .

What is the difference between AMR and SRMR?

It already sounded here and there: The Silk Road Mountain Race is different from the AMR simply because of its length and the tougher climatic and topographical conditions. It is not only physically more demanding, but also mentally more demanding.

In Kyrgyzstan, temperatures range from -15 to +40 degrees Celsius and mountains whose ascents can last almost 100 km and whose serpentines are then immensely steeper and (thanks to landslides) also more difficult to climb.

The Atlas Mountain Race feels a bit more technical, has more trails and challenges the MTB rider(s):in more. The Silk Road has that too, but here it’s more the long distance and the willingness to suffer through several hundred kilometres of stones and corrugated iron.

The supply situation is also different: in Morocco, water is a big issue and rather difficult. This is not the case in Kyrgyzstan and water is usually readily available. On the other hand, the distances between supply points are not as long in Morocco as they often were in Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan is also more remote and lonely than Morocco and has less infrastructure.

In any case, both are very good and beautiful races, worthwhile for their landscapes and challenges.

But both are NOT gravel races or anything like that 🙂 You need real bikes like hardtail MTBs or even fullys.

What’s next?

Good question! Nothing for now, because we have to take care of our families first, who have been supporting us for many months, so that we could prepare and ride the Silk Road.

Of course there are ideas, such as the Grenzsteintrophy or Tour Divide. But those are all still unlaid eggs. Maybe I’ll go more in the direction of bikepacking tours again. Just have a look, take part in smaller events here and there. In any case, I’ll stabilise the fitness level and then ride up again depending on the event.

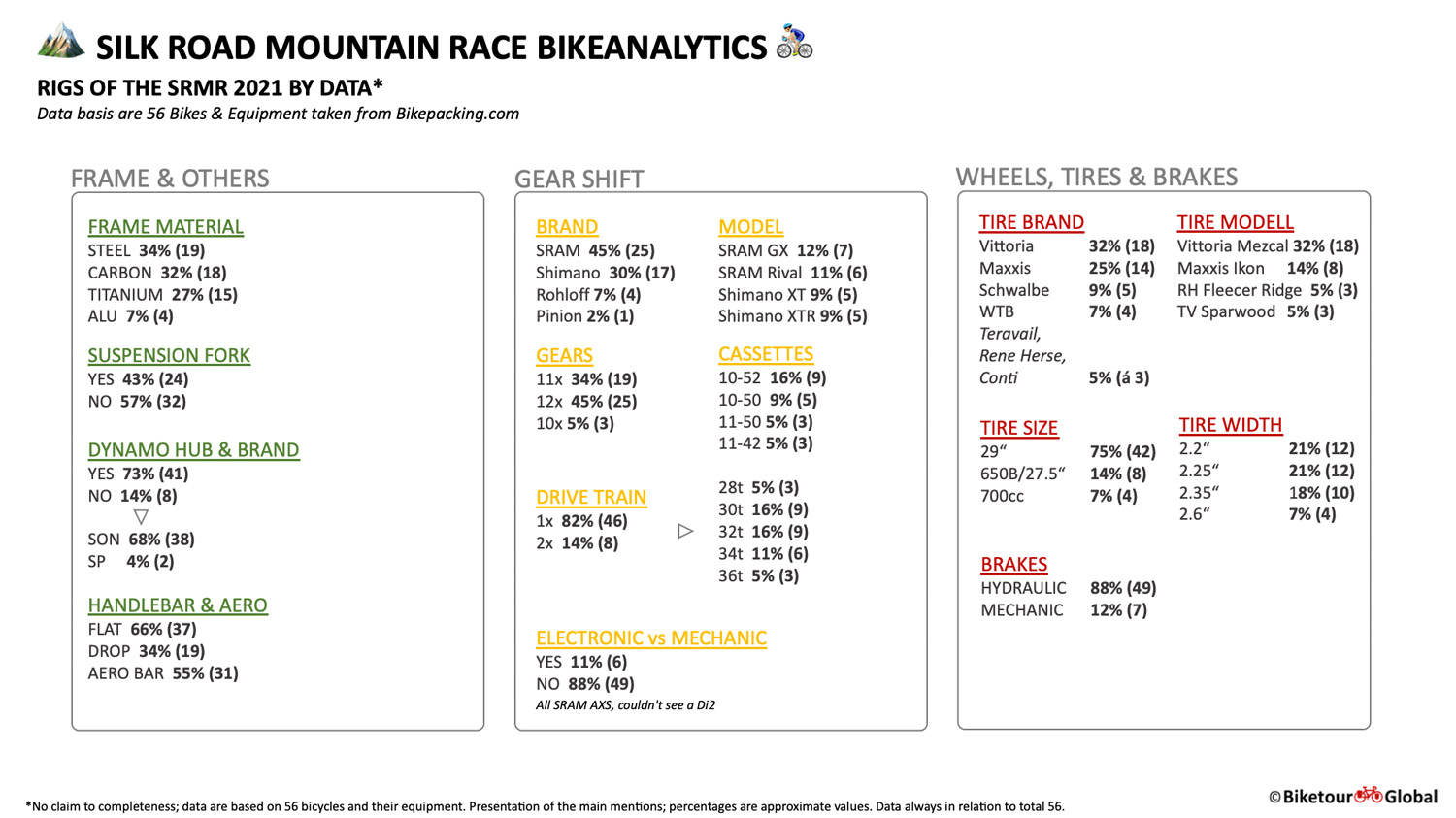

Excursus: Bikeanalytics Silk Road Mountain Race 2021

I have again looked at the SRMR’s bikes and evaluated them in terms of their equipment. In total I was able to evaluate 56 bikes, based on the article by Bikepacking.com colleagues “Rigs of Silk Road Mountain Race 2021”.

This is quite interesting for all those who are interested in the equipment and technology and who might also want to prepare their bike for races of this kind.